Siham Muntasser

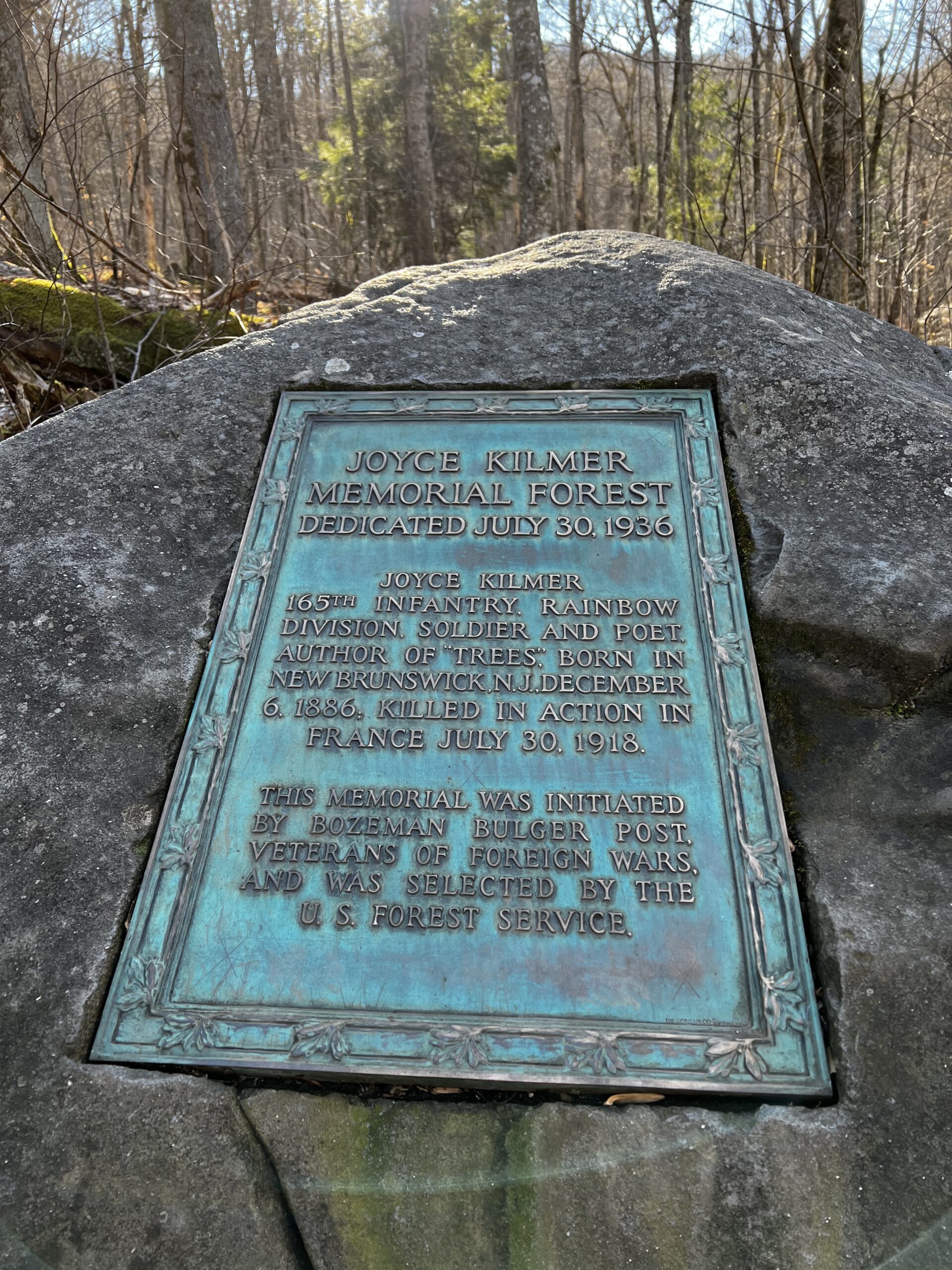

The Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, part of the Nantahala National Forest, is a very special place in so many different ways. It is dedicated to the memory of Joyce Kilmer, a soldier and a poet, who died in France in 1916 in a combat mission during World War I. He is the author of the poem Trees. To immortalize his love for trees, the forest was saved from timbering by an act of Congress. This park is one of the very few remaining places in the United States with trees as old as 400 years. It has more than 100 tree species with some more than 20 feet in circumference and 100 feet tall.

The forest is unique in many different ways. It is out in the wilderness, and the vegetation is thick and ragged. Then you see these enormous trees, although few are left. What is most striking is how tall they are; they have large knots, and the wood is beautiful. There is so much beauty in these tall, dignified beings with all their knots, aging so gracefully. Trees in the winter have their own special magic, magnifying the knots and the bark. Nature is so very evocative! Getting older is a scary process. It is reassuring to realize that we can be beautiful with all our knots.

The Joyce Kilmer Memorial forest makes us realize how much our forests have changed in the past 200 years. Historical writings describe the U.S. forests with settlers galloping their horses. In most forests today, such a ride is no longer possible. The younger trees are too close to each other and smaller in diameter. However, when you see this forest you clearly see that 400 years ago, the trees were much larger, with much more space in between. The comparison allows us to see the changes in our ecosystem quite clearly. We have eradicated most of our original native trees in less than 100 years, changing the ecosystem forever. What the consequences are for humanity is hard to tell. Deforestation is a calamity impacting many places on earth. From the Amazon rainforest, to the Tibetan plateau, to our forests in North Carolina, cutting trees is an ecological disaster of immense proportions. Our forests are very important components of life on Earth. Trees in forests are particularly important. Trees produce oxygen and remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in large amounts. Sadly, when trees die, they release the stored carbon back into the atmosphere. Atmospheric gases trap heat and increase the atmospheric temperature. Burning fossil fuels and deforestation are the two most important causes of global warming and climate change.

Trees teach us a lot about resilience. They help each other, they look after stumps. Trees adapt, recover, and sometimes move due to lack of suitable habitat.

The Dalai Lama warns us that if we don’t intervene, we will see the gradual breakdown of the fragile ecosystems that support us resulting in an irreversible and irrevocable degradation of our planet Earth. He states: “When the forests in Tibet die, a whole nation suffers. And when a people suffers, the whole nation suffers. We need forests for our health as well. When we go for a walk in a forest, fresh air is healing. We need green forests. They are nature’s great gift. Forests are good for our souls. In the forest we find the calm that our brain needs for regeneration. Forests are water reservoirs, home to many creatures and plant species, and are important as an air-conditioning machine. They are a mirror of the diversity of life.” This is emphasized by Pope Francis in his Encyclical Laudato si’ and says: “The interdependence of all creatures is God-given. The sun and the moon, the cedar and the field flower, the eagle and the sparrow-the myriad of differences and inequalities is evident that creatures are not self-sufficient, but exist only in dependence on each other and complement one another in mutual service.”

Sadly latest data indicate that global warming is worsening. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its “bleakest warning yet”, saying the climate crisis was accelerating rapidly. IPCC emphasizes that if we take action now, we have a chance of avoiding its worst ravages. Doug Tallamy, in Nature’s Best Hope, says that homegrown natural parks could be a solution. Paul Hawken in his book Regeneration, affirms that ending the climate crisis in one generation is possible if action and policy are weaved with justice and scientific knowledge of the role of biodiversity.

David Attenborough in his book, A Life on Our Planet, discusses the Planetary Boundaries Model, based on a study of resilience of ecosystems across the globe. The study has identified nine critical thresholds hard-wired into Earth’s environment, nine planetary boundaries. Four of these have already been pushed beyond acceptable safety. These are: excessive use of fertilizers, excessive conversion of natural habitats into farmland, global warming, and rate of biodiversity loss. Attenborough discusses the importance of achieving a more balanced life with nature, using a more circular economy with less waste while maintaining minimum requirements of human well-being.

The Doughnut Model is an enticing prospect for a safe and just future for all, he says. It consists of an outer circle containing the nine planetary boundaries and an inner circle, which is a social foundation with emphasis on the importance of good housing, healthcare, clean water, safe food, access to energy, good education, an income, a political voice and justice.

While individual lifestyle changes alone will not help abate the worst impacts of accelerating, runaway climate change, we won’t make the big systemic changes needed, without them. Collective individual lifestyle changes can really add up, if we all do a little.